Offering Bread and Roses for Nearly 200 Years

The slogan “Bread, and Roses, too” is at the heart of every philanthropic organization and cause in the United States. The term was coined in 1910 when factory inspector Helen Todd gave a speech during an automobile campaign for women’s suffrage in Illinois. She proposed that giving women the vote would “go toward helping forward the time when life’s Bread, which is home, shelter, and security, and life’s Roses, such as music, education, nature, and books, shall be the heritage of every child that is born in the country…”

Unfortunately, universal suffrage did not provide this heritage for all children, but a look at philanthropic activities throughout the world shows that these are the very things that charitable people with means hope to provide for those without.

In Santa Barbara, generous benefactors have historically fostered a culture of giving, one that has fueled a rich sense of community. Whether it’s giving time, money, expertise, or just plain back-breaking labor, philanthropy in Santa Barbara has created a strong societal unity and sense of belonging. From delivering meals to underwriting symphonic performances, the philanthropists of Santa Barbara have been providing bread and roses for our town since its inception.

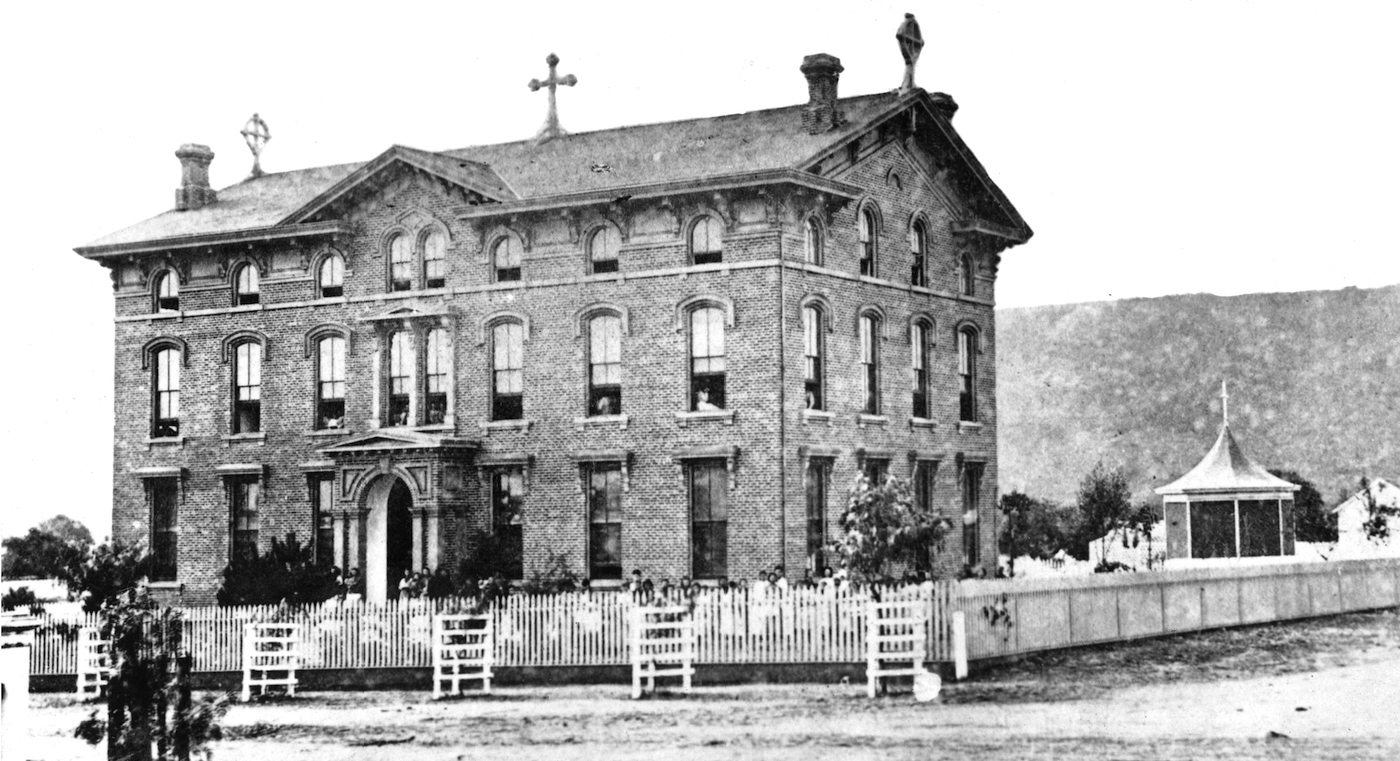

A look back at Santa Barbara’s Spanish and Mexican past finds a culture of hospitality and neighborliness that provided for the less fortunate in the community. After California became part of the United States, Bishop Thaddeus Amat centered the diocese in Santa Barbara and arranged for the Daughters of Charity of St. Vincent de Paul to open St. Vincent’s orphanage and school in 1857. Still in existence today, St. Vincent’s is the oldest charitable organization in Santa Barbara. It currently provides affordable housing, early childhood education, and familial support and enrichment opportunities.

Beyond the churches and the county and civic governments, Santa Barbarans themselves founded dozens of charitable organizations. Community galas and local dramatic and musical performances, which benefited a variety of humanitarian projects, became popular. Beginning in the 1880s, the town saw dozens of festivals like the 1890 Trade Fair to build Cottage Hospital and the annual Valentine’s Day fairs of the St. Cecilia Club (today’s Cecilia Fund) to pay hospital expenses. In 1911 the famous danseuse Inez Dibblee, daughter of a local pioneering family, presented three dances to further the fund for the Rincon Causeway. In 1913, the Flying A Players performed live on the Potter Theatre stage to support the municipal band directed by Caesar LaMonaca.

Santa Barbarans grew roses for the community through the creation of organizations such as the horticultural and natural history societies, the public library, community music organizations, and art clubs. Probably the crowning achievement in the arena of cultural philanthropy was the creation of the Community Arts Association and its various branches under the leadership of Pearl Chase and Bernard Hoffmann in the early 1920s. Their ideas and enthusiasm inspired the involvement of dozens of other prominent and talented men and women residing in Santa Barbara at the time. Besides promoting civic beautification efforts, the organization involved local citizens in art, drama, music, and dance, and brought world renown teachers and performers to town.

Hundreds upon hundreds of volunteers gave their time, money, and expertise to create this very exciting and rewarding community entity, which brought people from all walks of life together in communal harmony. Thousands of Santa Barbarans found their lives enriched by the bouquet of programs offered by the Community Arts Association.

Today, there is a wealth of philanthropic organizations in Santa Barbara, several of which have their roots in the long ago. Besides the churches and various fraternal organizations that have a charitable component, the longest standing philanthropic organizations in Santa Barbara include St. Vincent’s, 1858; Salvation Army, 1883; Cecilia Fund (St. Cecilia Club, 1891); Family Service Agency (Associated Charities, 1899); Visiting Nurses Association, 1908; Santa Barbara Museum of Natural History (Museum of Comparative Oology, 1916); Community Arts Music Association (Civic Music Committee, 1919, and Music Branch of Community Arts Association, 1921); Santa Barbara Foundation, 1928; Santa Barbara Historical Museum, 1929; and Unity Shoppe (Council of Christmas Cheer, 1930).

This book highlights the work of 52 of Santa Barbara’s current nonprofit institutions. Successful philanthropic organizations come about due to great leadership, generous benefactors, and community involvement. The following is the story behind one historic entity that has been enriching the lives of Santa Barbarans since 1907.

Neighborhood House, Margaret Baylor, and Recreation Center

In 1907, the Young People’s Club Association was formed to provide both boys and girls with recreation, education, culture, practical skills, music, art, and jobs for those Santa Barbara children whose families could not provide these amenities. Mrs. Elizabeth McCalla (wife of Admiral Bowman McCalla) recruited prominent women of the city to help fund the creation of the club, which was being promoted by many of the teachers in the public schools. Ednah Rich, principal of the Anna S.C. Blake Manual Training School, became treasurer, and Mira Morgan, former principal of Franklin School and truant officer, assisted in leadership.

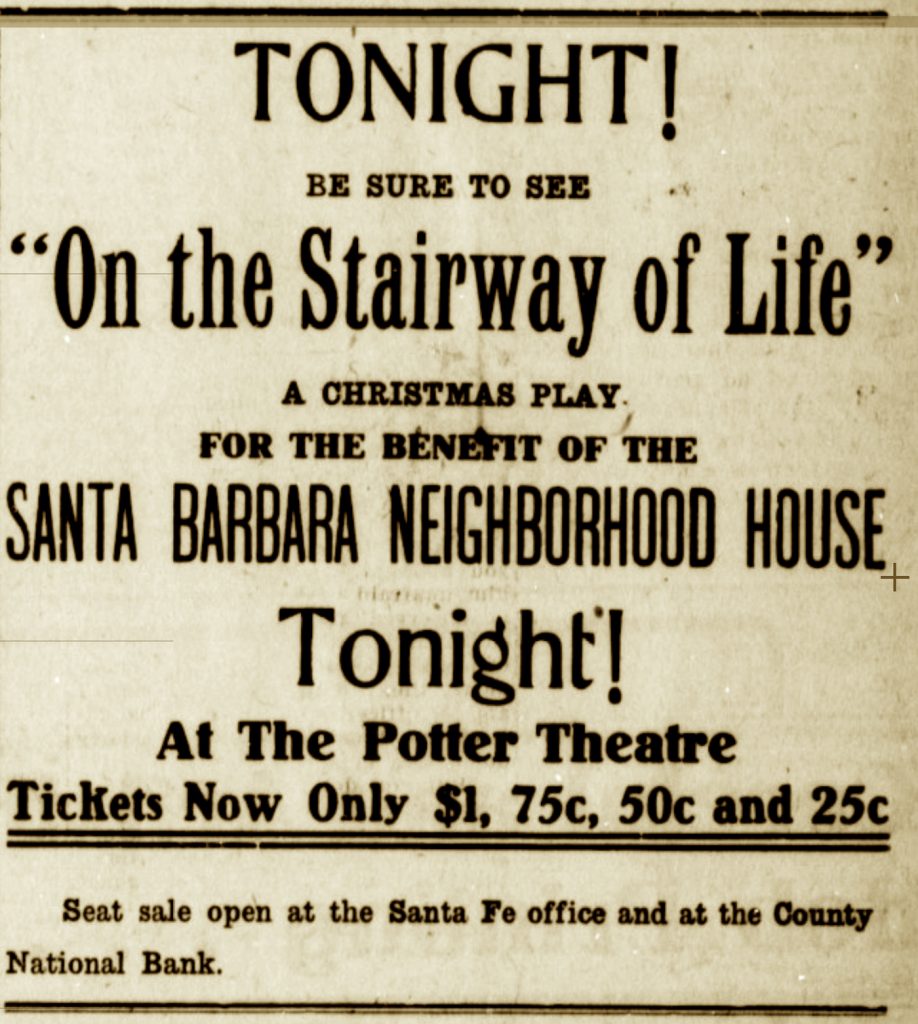

Twenty generous women covered the expenses for the first year, and the Association solicited association membership fees on a sliding scale from $2 to $100, with the latter securing a life membership. Many people offered their services, and others supplied furnishings and other necessities. Over 100 people happily joined to support the Association, and many benefits were given to raise funds. In 1908, Santa Barbara and Montecito society, for instance, participated in a play called “On the Stairway of Life” at the Potter Theatre, with all receipts going to the Club.

The Club became wildly popular during its first year and at the end of 1908 changed its name to Neighborhood House to more accurately reflect the intent and breadth of its programs and clientele. In 1910, it joined up with the 1899 Associated Charities (which became Family Service Agency in 1953) and moved to the Arellanes Adobe whose extensive property took up half the block at 800 Santa Barbara Street.

Relying on volunteer instructors, a typical week at Neighborhood House in the early days offered the following: Military drill on Mondays; block printing and gymnastics on Tuesdays; practical electricity and camp talks on Wednesdays; boat building for boys and sewing and dressmaking classes for girls on Thursdays; and metal work and mandolin classes on Fridays. All of these classes commenced after the school day ended at 3 pm or in the evenings at 7:30 pm. The weekends saw supervised play and talks on various topics as well as musical evenings. During the summertime, Neighborhood House helped boys find employment. One summer, Mr. Post, who was a city truant officer, took 20 boys to Ojai where he set up a summer camp, and they earned money by picking fruit.

In 1910, Miss Margaret Baylor came to Santa Barbara to take over the superintendency of Neighborhood House. Baylor had been active in social work in Cincinnati, Ohio, for several years. During a 1907 visit to her sister Sophie who lived in Santa Barbara, she had suggested the formation of a club for local youth.

During Baylor’s tenure, Neighborhood House would expand its programs and focus on wholesome recreational activities. She was directly responsible for the creation of the Carrillo Recreation Center and the Margaret Baylor Inn (today’s Lobero Building). Described as a woman with a rare gift of the understanding of human needs and a passion of love for mankind, she created a lasting legacy of social service in Santa Barbara.

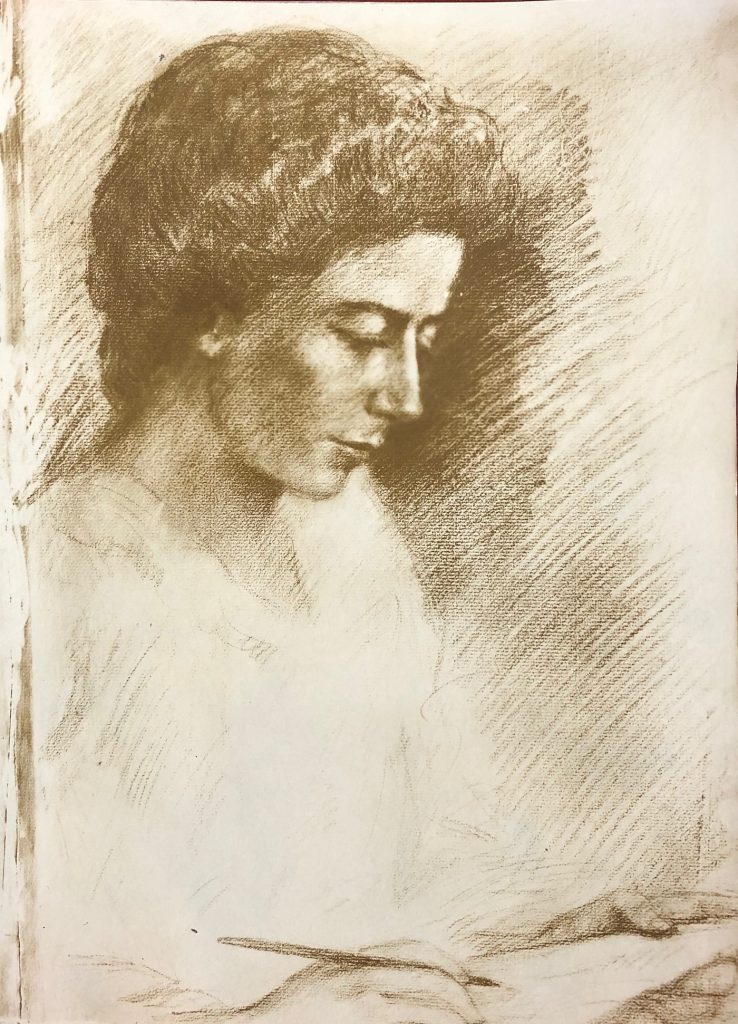

Margaret Baylor

Margaret Baylor was the 11th (and last) child of Louisa Dennison Wadsworth and Charles Gano Baylor, both of prominent and historic East Coast families. Louisa’s heritage dated back to colonial days, and she was related to Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. Members of Charles’ family were important in medicine, law, agriculture, and politics in Virginia, Kentucky, and Texas.

By the time Margaret was born, her father’s varied careers had spanned stints as a lawyer, U.S. Consul to the Netherlands, U.S. Consul to England, advocate of free trade for the Southern states, editor and founder of a weekly journal called “Cotton Plant,” and song writer. During the Civil War, he was European Trade Consul for Georgia, but when he joined General Wayne and others to form the Georgia Peace Party in 1864, the Confederate government ordered his arrest. He and his family had to flee on a blockade-runner from Wilmington, Delaware, to New York City.

The intervening years cannot have been kind, for when Margaret May Baylor was four years old in 1880, her father was committed to McLean Asylum for the Insane in Somerville, Middlesex, Massachusetts. Four of her siblings had died before adulthood, and her mother had found work as a music teacher. It’s doubtful that her father returned to the family, but he eventually made his way to Rhode Island, home of his mother’s Gano family clan. He even ran for governor of Rhode Island in 1894. Meanwhile, his wife listed herself as a widow. In 1906, Charles Gano Baylor died. By then, Margaret, age 30, had moved to Cincinnati, the home of Woodward College, her father’s alma mater. There, she would engage in social work as part of Union Bethel House.

Margaret’s calling to social service had started early. Following in her sister’s footsteps, she volunteered at girls’ clubs in Boston, and then in Washington, D.C. In New York, she directed vacation camps and clubs for the girls of the East Side. When she moved to Cincinnati, Ohio, she was thrust into organizing relief measures for the great Cincinnati Flood of 1906. Her work was so extraordinary that it was still remembered years later. When Dayton, Ohio, experienced a similar disaster, she organized relief there as well.

In 1908-09, she supervised the construction and opening of the Anna Louise Inn, a residence hotel for young business and professional women. Charles P. Taft, brother of the future President of the United States, William Howard Taft, donated the site and funds for the five-story building that would house 120 women in single rooms. It was named for Taft’s daughter, Anna Louise Taft Semple.

Margaret Baylor became its superintendent and it was fully occupied from day one. With its homelike tone and the freedom “accorded its guests within the bounds of propriety,” it became regarded nationwide as a model for such efforts. The inn offered single rooms, a library, reception, dining, cooking, and laundry rooms for use of residents. Rates of room and board included all accommodations and ranged from $2.75 – $4.25 a week for single rooms. To qualify for residency, girls could only earn a maximum of $10 per week. Under Baylor’s supervision, they employed self-government, as well.

Santa Barbara Beckons

In 1903, Margaret’s older sister by 20 years, Sophie Frances Baylor, moved to Santa Barbara. There she became private secretary to Charlotte Bowditch, a wealthy woman from Massachusetts, who owned property in Santa Barbara and Boston. Both Sophie and Charlotte were active members of Neighborhood House Association and on its board of directors. In 1910, when Mira Morgan, a founder of the organization and matron of Neighborhood House, left for Los Angeles, the directors hired Margaret Baylor.

The Morning Press headline in July 1910 read, “MISS BAYLOR BRINGS RARE EXPERIENCE TO NEIGHBORHOOD HOUSE MANAGEMENT.” Already flourishing, the organization was about to blossom into a popular civic center with dozens of programs for Santa Barbara. That summer, the old Arellanes-Elizalde-Quintero home had been completely renovated into an appealing homelike clubhouse complete with stage and assembly areas, and the grounds had been graded for a playground area devoted to volleyball, tennis, basketball, baseball, and croquet.

Under Baylor’s direction, Sunday teas and band concerts by Caesar LaMonaca’s band were instituted. She initiated supervised public open-air dancing and continued the activities of the boys’ and girls’ clubs, meeting with each group to help plan new activities and classes. By December, businesswomen organized a club at Neighborhood House, and a men’s club was initiated as well.

That year, 50 children from Neighborhood House sang Christmas carols in the corridors of the Old Mission on Christmas Day and, after a reception at the mission, continued on to serenade “friends” of the House like Mrs. Christian Herter. The previous two days, the children and their parents had been treated to Spanish music and dancing, a beautiful Christmas Tree, a visit with Santa, and best of all, presents to open in front of the cozy fire. This was, perhaps, the genesis of the Community Christmas tradition, still evidenced by the Community Tree of lights.

Over the years, Margaret’s activities were not confined to Neighborhood House. She became a member of the juvenile court committee and attended trials of young women to show support and offer a measure of protection. She basically served as an unpaid police officer, and the chief of police consulted with her in all cases affecting women and children. She originated the movement that resulted in the appointment of a woman as a regular paid member of the police force. She also introduced certain city ordinances that dealt with social issues.

As for Neighborhood House, as each year passed, new programs were added to the organization, like the Entre Nous Club for girls from 16 to 20 who were planning a beach tea at Hope Ranch in May. Always the emphasis was on wholesome, supervised recreation and activities. Each summer Neighborhood House sponsored a beach playground and a bathhouse, all properly supervised by Thornton Hopler. The annual Kirmess in August lasted several days and featured locally produced performances at the Potter Theatre, all to benefit Neighborhood House.

The Recreation Center

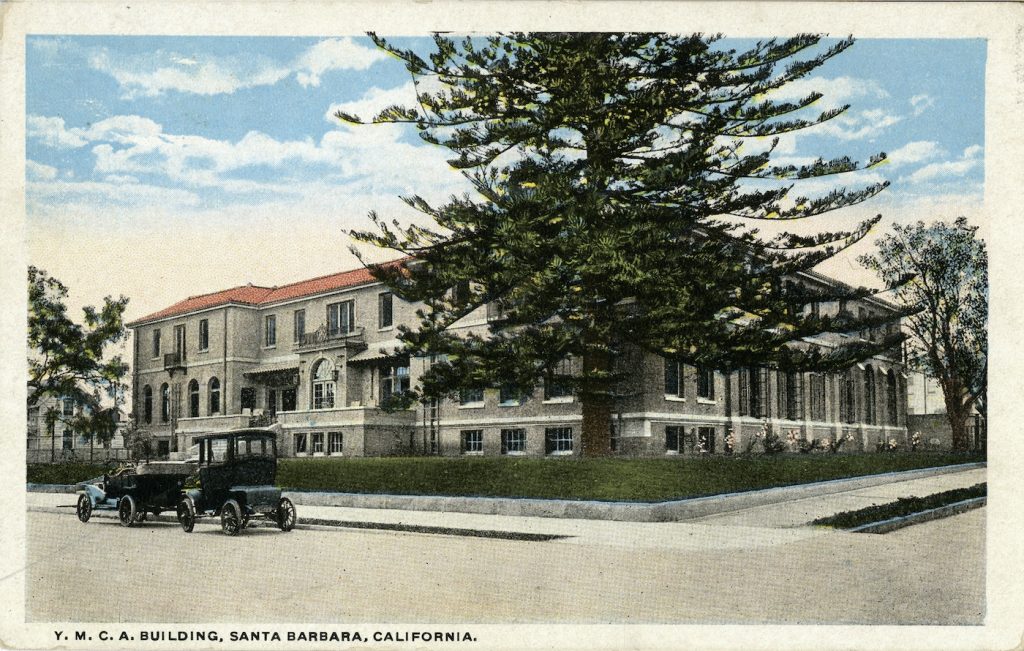

As Neighborhood House increased in programs and popularity, Margaret Baylor and others began to dream and plan and work towards a new facility to house its programs. On May 24, 1913, the Morning Press was able to announce that a recreation center and auditorium was to be built on land purchased from the Natural History Society on the corner of Anacapa and Carrillo streets. Architect J. Corbley Poole donated plans for the brick Craftsman-style building and supervised the grading when ground was broken in December 1913.

On August 12, 1914, the beautiful facility opened its doors to reveal women’s clubrooms, a public reading room, young men’s clubrooms and an auditorium with spring floor for dancing. Upstairs was the superintendent’s suite plus several single bedrooms for the use of young women who were strangers in town looking for employment. At the dedication ceremony, Margaret Baylor was among the speakers and explained the necessity behind creating this facility, which was open to all the people of Santa Barbara.

“Some of the social workers are considered somewhat ‘hyped’ on the subject of recreation,” she said. “But we have in our minds the picture of the blazing lights of commercialized vice and pleasure in contrast with the darkened church and vacant school. Jane Addams [famous Settlement House worker in Chicago] says recreation is stronger than vice and the only antidote to vice. Here we hope to attract, every day and every night, happy, laughing fun to fill the spirit against all who long for unwholesome pleasure.”

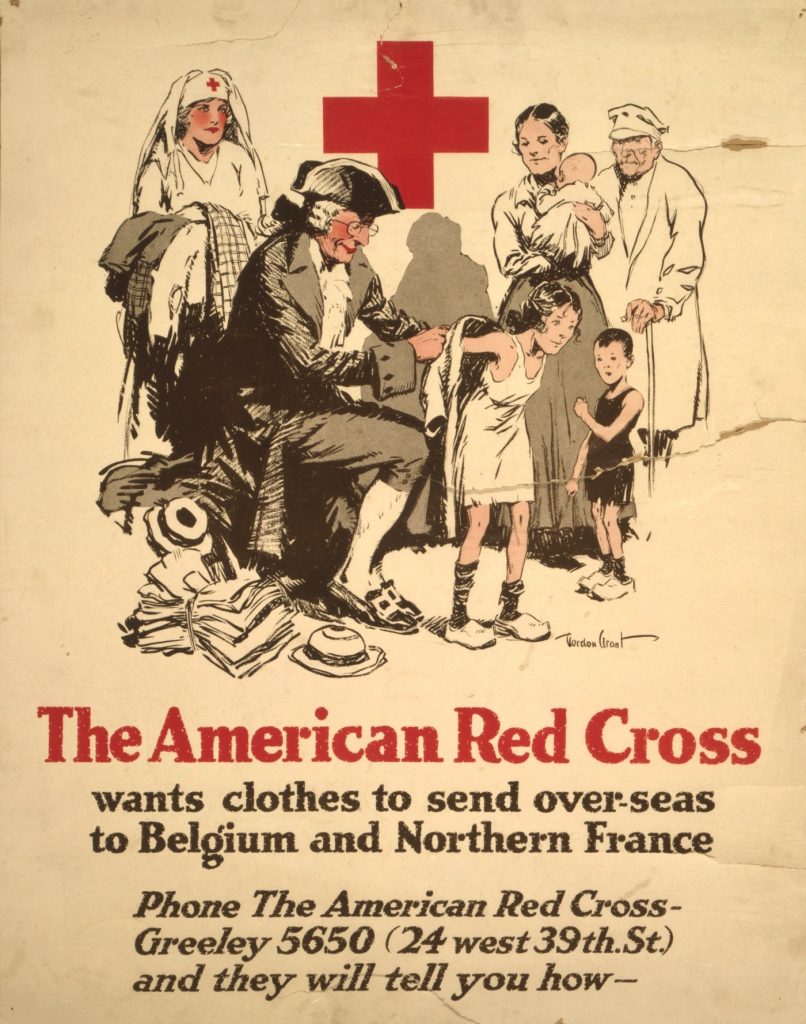

War had broken out in Europe on July 28, 1914, and the Recreation Center soon found itself sharing its facilities with war relief work. By November a group of women began spending one day a week sewing invalids’ clothing and bedding, making bandages, and knitting for the relief of Belgium. A Sack of Flour club was organized, intended for those who were unable to give large sums. Sacks of flours at $1.65 each could be purchased and sent to the train depot for eventual transport to Belgium. For those who were disgruntled that money and help was being sent out of the country, they were reminded that when San Francisco was stricken by the fire of 1896 leaving 200,000 people destitute, a shipload of supplies was sent by Belgium. “With now 7 million Belgians in need of aid,” opined the press, “California, above all other states, now has an opportunity to show its gratitude.”

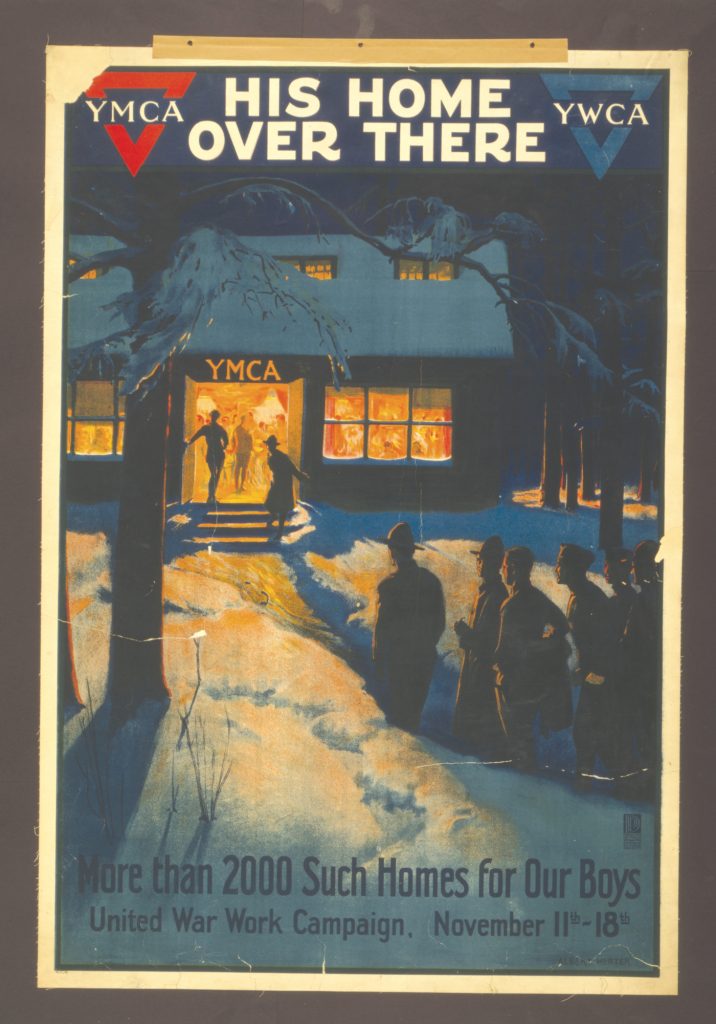

By 1917, when the United States entered the war, the entire facility was taken over by the Red Cross, which had been organized in Santa Barbara in March 1917. Baylor was one of 36 directors of the organization. A separate and additional building was constructed at this time for the use of the Red Cross, who needed additional quarters. It was intended to become a gymnasium when the war ended.

Praise for the Center

After the war, in October 1919, King Albert of Belgium visited the Recreation Center during his three night sojourn in Santa Barbara, part of a month-long diplomatic visit to the United States. While here, he wanted to see the building in which so many Red Cross articles were made for the Belgians during the war. “It seems wonderful that such a building is built for all groups of the people of the community,” he said during his visit. “The building shows this city to be very progressive and democratic.”

Also in 1919, upon the death of Charlotte Bowditch, Neighborhood House, Recreation Center, and the two Baylor sisters received a great boon. In her will, Bowditch bequeathed $100,000 to her friend and companion, Sophie Baylor, and $15,000 to Margaret. She also gave them her home, furnishings and all, with the stipulation that after the death of the last sister, the property be donated for a museum or educational purposes as would be best for the community. Neighborhood House was given $20,000 for a girls’ gymnasium or any improvements the directors thought necessary.

On a February 1921 visit to Santa Barbara, Mr. L.B. Williams, a representative of the national Community Service organization, declared Santa Barbara’s Recreation Center to be the greatest in the United States. Williams was seeing a great nationwide awakening to the opportunity for national morale building through the discovery of the talents of the people and by providing opportunities for self-expression. He was also pleased that “the great-hearted philanthropists with large pocketbooks are now interested intensely in this leisure time movement.”

“The Recreation Center,” he avowed, “is making Santa Barbara a better place for all the people to live in, and, as Theodore Roosevelt said, ‘If we do not make this a good country for all of us to live in, it will not be a good place for any of us to live in.’”

In their annual report of January 1922, the directors of the Recreation Center announced that ten thousand people used the Center each month through clubs, lectures, meetings, and recreation. Plans, they said, were in the works for another expansion of the program, the construction of a residence facility for women and girls.

Unfortunately, Margaret Baylor never saw the completion of this dream for she died on January 15, 1924, after a long illness. It was left to others, spearheaded by Pearl Chase and Caroline Hazard to see the Julia Morgan-designed building made manifest. It was named the Margaret Baylor Inn in her honor.

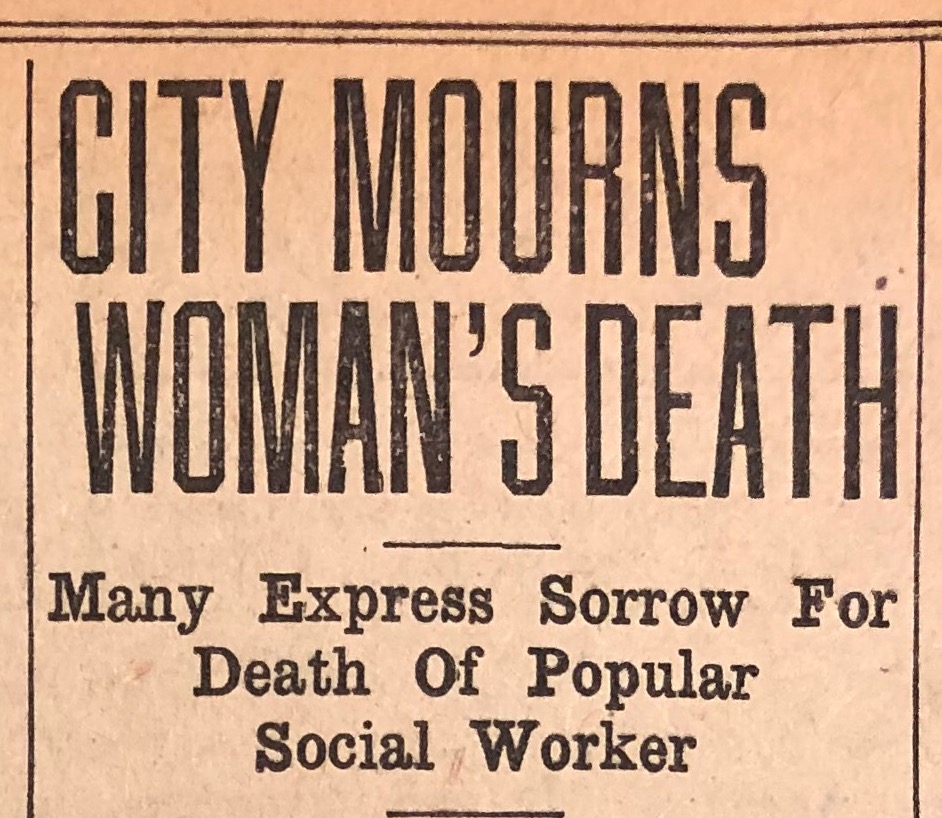

A City Mourns

Upon hearing the news of Baylor’s death, the entire city was struck dumb. Meetings were cancelled. There were widespread expressions of deep regret and sorrow from all members of Santa Barbara society. The Morning Press reported, “An entire city will pay final tribute to a sterling leader this afternoon when funeral services are read for Miss Margaret Baylor, pioneer Santa Barbara social service worker and founder of Recreation Center… Her death is mourned by those high and low in the scale of life. The love and kindness she dispensed during her long, active career, is reflected a thousand-fold in the expressions of praise that are heard on all sides.”

“Hail the hero workers of the mighty past!” was the opening line of the hymn whose words were a source of much inspiration for Margaret Baylor. The hymn reflected the emotions of the hundreds of friends who gathered at the service. “Heads were bowed in silent prayer, eyes filled with tears, and men’s shoulders shook with grief as the last notes of the hymn died away,” reported the newspaper.

In a tribute to Margaret Baylor, Alice M. Simrall wrote, “[She was] a woman who saw a vision and dreamed a dream, and with love and power wrought the vision and the dream into reality for the service of mankind. She came into the world with a message of truth, and through her life and her work she translated that message into terms that all could understand… In the lovely city of Santa Barbara, on the shores of the blue Pacific, stands a beautiful building…, which, in tangible, visible form, is a message from Margaret Baylor to her fellow men, Recreation Center, Santa Barbara’s Community Club House.”

As the strains of the of the recessional music faded away, and the mourners slowly left the church, floral tributes heaped high on the altar of Trinity Episcopal Church bore witness to the esteem felt for Margaret Baylor, who had brought an abundance of bread and bounteous bouquets of roses to Santa Barbara.