The Shortest Distance to Making a Difference

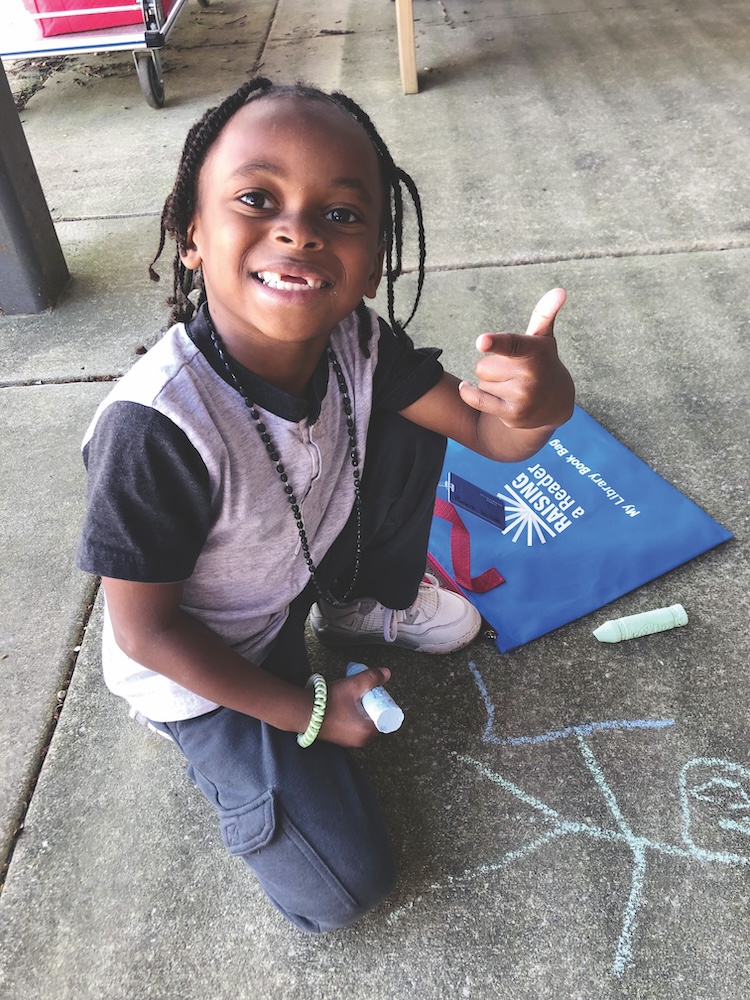

In 2000, Judy Koch learned something surprising about many of the workers in her sheet metal factory in Fremont, California: They didn’t read books with their kids. As a former junior high English teacher now on a second career as a manufacturing CEO, Koch wanted to instill a love of reading in her employees. Her idea? Give away high-quality storybooks for free.

This simple act created a tidal wave of expanded family literacy among the mostly Latino men who worked on the factory floor.

Sterling Speirn, who was looking for innovative ideas as executive director of the Peninsula Community Foundation (now the Silicon Valley Community Foundation), was alerted to this experiment and quickly adopted it as part of the Foundation’s Center for Venture Philanthropy. A trial program with the San Mateo County library system was very successful, and the program continued to grow.

Twenty-five years later, this project – Raising a Reader – has changed the literacy and reading culture of more than a million families in 33 states. With its low-cost method for preparing children for kindergarten, Raising a Reader demonstrated that “reading time” fostered parent-child bonding as well as critical cognitive development.

“Judy used to tell me that when her employees went home at night, their children would run to the front door and say, ‘What book did you bring me, Daddy?’” Speirn recounts. By equipping them with books and bags, “she had made them heroes in their own homes.”

The success of this program reminded Speirn, who had also been a teacher before entering philanthropy, that the small step of exposing kids to reading early created long-lasting, permanent changes far beyond literacy.

“If you want to do anti-poverty and racial justice work,” he adds, “a program like this is the most cost-effective way.”

Theory of Change

We live in a moment of radically expanding complexity. The volume of information (and misinformation) comes at us like a firehose from every screen, even as we try to adjust to accelerating social, political, environmental, and technological change. The question then becomes: How do we make sense of our philanthropic choices as we seek to make meaningful change?

The success of Raising a Reader offers at least one major insight: No philanthropic step is too small, or too soon. And as Judy Koch demonstrated, starting with what is right in front of you is often the shortest distance to making a difference.

“Philanthropy is so personal. I always want to encourage donors to start where they are at, with the issues they are most passionate about,” says Tammy Sims Johnson, Vice President of Philanthropic Services at the Santa Barbara Foundation. By leaning into one’s passion, curiosity, and professional expertise, continues Johnson, donors “will find the niche where they can make a significant, meaningful difference, whether it’s small-scale or large-scale.”

Johnson points to the work of Carrie Towbes, Ph.D., a licensed clinical psychologist with expertise in children and youth. Her background as a special education teacher and her clinical experience in a wide array of settings including schools, hospitals, community clinics, and private practice, enhanced her awareness that local mental health professionals were burning out at an alarming rate, imperiling the entire system of support.

Trusting her experience, Towbes saw an opportunity for study and innovation that led to the creation of the 4R Fund, in partnership with the Santa Barbara Foundation, dedicated to the long-term, holistic support of mental health professionals. The 4R’s stand for recruit, retain, rest, and recuperation.

Towbes is also president of the Towbes Foundation, a multi-generational family foundation that has generously supported many nonprofits in the Santa Barbara area. While the Towbes Foundation has historically funded many nonprofit sectors, they currently target Towbes’ areas of expertise. Towbes emphasizes that it was “my clinical experience that informed the direction of my philanthropy.”

Yes, and…

The social and political developments of the last few years might prompt a contradictory response: How might we acknowledge the systemic, large-scale, often multi-generational nature of our problems, without losing sight of the tangible, concrete issues right in front of us?

Extraordinary gifts that can change the game are necessary contributions. Two recent examples, just in the healthcare field, include $1 billion donation donations from Dr. Ruth Gottesman to the Albert Einstein College of Medicine in the Bronx, and from Mike Bloomberg to the Johns Hopkins Medical School. These gifts will make it possible to educate a more economically diverse class of future physicians, which will in turn support more community clinics and improve the healthcare of communities of color.

At the same time, more modest gifts can have an incredible influence on smaller organizations. Sneha Dave is the 26-year-old founder and CEO of Generation Patient, an advocacy and support nonprofit serving young adults with chronic illnesses. In a recent essay in the Chronicle of Philanthropy, Dave makes the case that nonprofits with budgets under $1 million are often ineligible for certain kinds of grants. Dave points to MacKenzie Scott’s extremely generous funding of hundreds of nonprofits with grants of up to $2 million, which excluded lean organizations like hers, with a staff of three and an annual budget of $450,000.

In an interview, Dave said that most smaller organizations like hers depended on smaller donations, “which could make a huge impact on our work.” She encouraged donors to consider supporting less well-known organizations by helping with immediate needs that could lead to longer-term impact. In her Chronicle essay, Dave expressed gratitude for a foundation “which paid for a leadership transition consultant and executive coach for me. I’d never managed a staff nor had a manager myself, which made the additional coaching transformational.”

Or as organizational guru Daniel Stillman puts it in a recent blog post on his Conversation Factory website, we often think that “the first step towards a big goal needs to be significant and worthwhile. It had better make a dent in the problem. But physics tells us that we just need to find a really really really small thing that gets us started and gets the chain reaction going.”

How big a reaction? “It’s hard to imagine, but starting with a domino just five millimeters tall, it would take just 29 progressively larger dominoes to knock over a domino the size of the Empire

State Building.”

Efficacy of Giving Smaller: Visibly, Tangibly, Ongoing

Robin Mencher, CEO of Jewish Family and Community Services East Bay, is eager to see large-scale change that will be more supportive of those in need. That future, she believes, is likelier to take place “not through sudden, radical shifts, but through the accumulation of thousands of micro-changes.”

The reason? “Stability is a building block for bold change,” says Mencher, who notes that stability can seem counterintuitive in nearby Silicon Valley, where “there is a culture of disrupting things and seeing what happens… But for charities and nonprofits to take ‘good’ risks, there needs to be stability. And nonprofits get stability by not having to worry about making payroll.”

In other parts of the charity ecosystem, huge impacts are being made by the accumulation of thousands of micro-donations. A recent NPR story highlights the incredible gains for nonprofits when customers “round up” a purchase as a gift. The Taco Bell Foundation, which funds nonprofits like the Boys & Girls Clubs, noticed huge increases in donations when people had the opportunity to give less than a dollar. In 2019, the first year they tried this approach with the 7,500 U.S. restaurants, they doubled their contributions.

Bart Burstein and Leslie White created the Pace Able Foundation in Palo Alto to focus their support of nonprofits (and a few for-profits) in health, education, and capacity-building, mostly in the developing world. Burstein had a successful career in tech, and White worked in both education and tech before they retired to focus on philanthropy.

One of their advisors at the time was Judi Powell, founder and principal of Seven Hills Philanthropy, and previously a senior leader at Silicon Valley Community Foundation and Pacific Foundation Services. When they asked her for strategic advice, “Judi told us to give unrestrictedly. Try not to put too many impediments in the way of grantees.”

As they learned more about the organizations they wanted to support, they took this advice to heart, funding a targeted group of nonprofits, and creating an ongoing partnership based on trust.

“With all the problems we saw, we asked ourselves, ‘How can you bear to focus on just one thing, when there are 100 problems confronting you,’” Burstein says. An answer, he adds, came from philanthropist (and former President) Bill Clinton: “Do what you care about.”

In a recent essay in eJewish Philanthropy, Barry Finestone, president and CEO of the San Francisco-based Jim Joseph Foundation, acknowledges these hundreds of problems at a moment of VUCA – volatility, uncertainty, complexity, and ambiguity. This term, originally used in the military, was introduced into leadership studies 40 years ago by University of Southern California professors William Bennis and Burt Nanus. Their argument was that effective leaders needed to avoid coveting simplicity at the expense of patience and self-reflection.

In his article, Finestone encourages philanthropy’s critical work of engaging complexity, which includes “strategic planning, and remaining focused on long-term goals and outcomes.” But he cautions that the perfect can be the enemy of the good, and that simply acting was sometimes the higher calling. “We need to train ourselves,” he writes, “to strengthen our adaptive ‘muscles’ so we are ready to quickly and effectively react to issues and unanticipated developments in as close to real-time as possible.”

Small Steps, Small Houses…

Across town from where Bennis and Nanus taught, on the Great Lawn of the West Los Angeles VA Medical Center at San Vicente and Wilshire, hundreds of struggling veterans have been waiting, sometimes for many years, for adequate housing within which they can heal and receive the care they need. Their experiences are the epitome of VUCA.

The visual overwhelm of so many unhoused neighbors evokes a hopelessness with the scope and scale of America’s social problems, and radical uncertainty as to what we can do, even as we motor to work in our air-conditioned cars.

In 2021, as part of a movement toward quickly offering “tiny homes,” the agency decided to replace tents with small but functional home-lets, moving past the immense complications and delays of well-meaning environmental and financial requirements.

The results were striking, if still small-scale, leading to improved physical and mental health, and more positive social engagement. John Kuhn, Deputy Medical Center Director for the VA Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System (VAGLAHS), acknowledges that “while this resource by itself does not solve homelessness… it is a critical tool to ensure safety.” By moving the process forward in a simple, meaningful way toward permanent housing, the VA “will offer Veterans a path to that destination.”

First Connect, Then Correct

Many of our social problems, research shows, are a result of a simple lack of connection. COVID made clear, and in many cases accelerated, an epidemic of American loneliness that directly correlates with mental illness, frayed social bonds, and even obesity. Social media, despite including the word “social,” has compounded that effect.

Funders, especially new ones, often see positive results when they simply get together to talk about giving – and then go ahead and give. Among the most effective social vehicles for funders, philanthropic advisor Judi Powell says, is the giving circle.

“For funders, especially first-time funders who might still be anxious about doing this ‘right,’ these relationships are really important,” she says. Among other things, these relationships “help build confidence and are an invaluable source of information about how to give and where to give. And of course they amplify the impact of a single funder by pooling the funds of many.”

The San Francisco based Jewish Community Federation and Endowment Fund (JCF), which raises and distributes funds for a variety of Bay Area and Israel-connected organizations, has leaned into the value of “social giving,” especially among younger donors.

“Our giving circles, which empower people of all ages, backgrounds, and incomes to actively participate in philanthropy, support individuals in coming together to pool their charitable funds, discuss shared values, learn about inspirational organizations, and make collective decisions about which organizations to fund,” said Rebecca Randall, Chief Philanthropy Officer of the Jewish Community Federation and Endowment Fund.

A young adult giving circle called The Bay Area Tribe, co-chaired by Moriah Jacobs, found that the simplest way to move from anxiety and uncertainty to productive action was coming together. The giving circle, she says, was “a safe and open space for people to be vulnerable and honest, which contributed to a really productive and engaged group.”

There is no one-size-fits-all philanthropy. Some people and institutions like to spread their bets, while others prefer to go deeply into one issue or community. Some look to explicitly change the game, while their peers seek to amplify what’s already working. In the end, the best and simplest solution is just to get to work.